Step Into Rome’s Past: The Story of 316 E 3rd Ave

Some homes shelter people. This one shelters stories. Standing proudly since 1883 in the heart of Rome’s Between-the-Rivers district, 316 E 3rd Ave isn’t just a beautifully preserved Victorian; it’s a time capsule built by one of Georgia’s most remarkable sons, Major Eben Hillyer. Every board, brick, and relic beneath the soil tells a tale of war, healing, family, and legacy. This isn’t a house you walk through. It’s a house that walks you back in time.

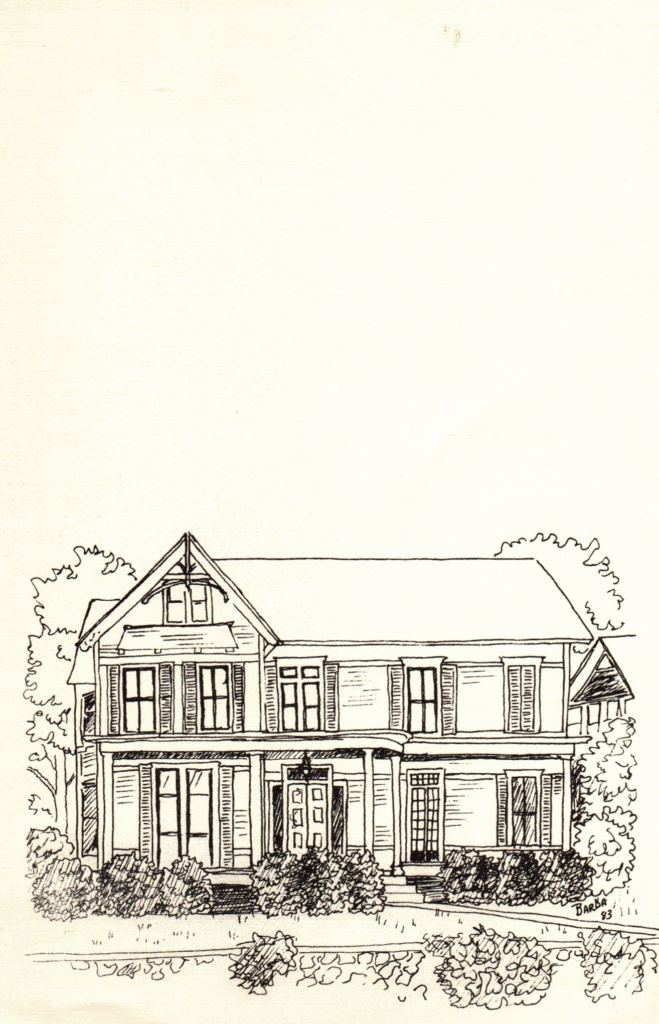

More than a home, 316 E 3rd Avenue is a living archive. Designed and built by Confederate surgeon Eben Hillyer, it speaks through its craftsmanship, its preserved details, and the stories still waiting beneath its floorboards. Tucked within Rome’s historic core, it stands as a testament to Southern resilience and the layers of history that quietly shape the present.

316 E 3rd Ave today, restored and

preserved, where Rome’s past meets its present.

1883: The Birth of a Home

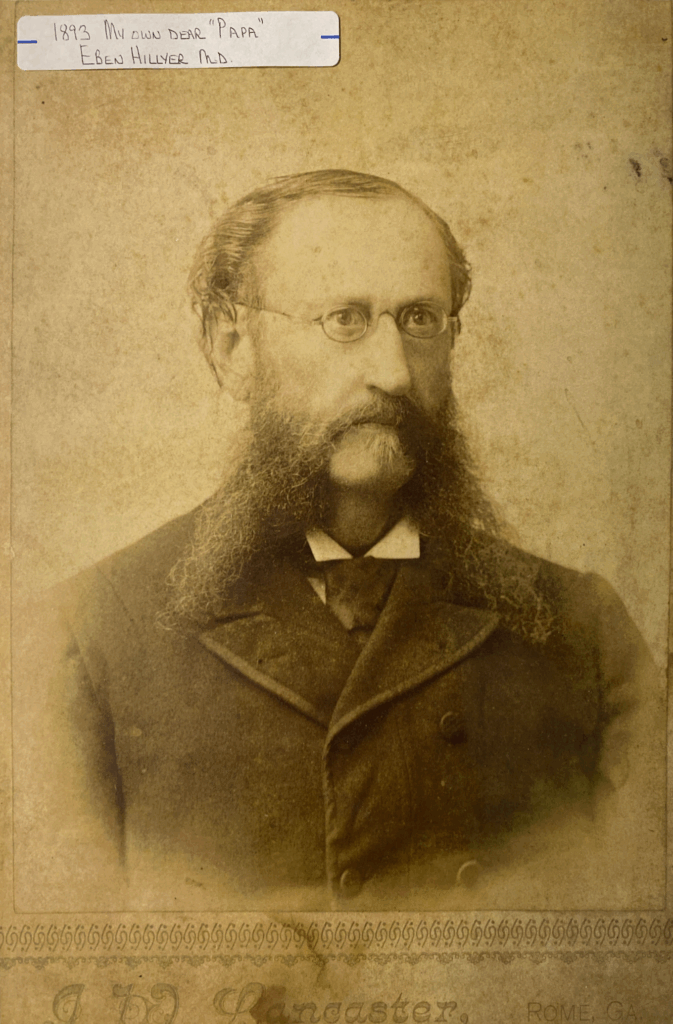

Born in Athens, Georgia in 1832, Eben Hillyer emerged from a family steeped in legacy, purpose, and Southern tradition. His father, Junius Hillyer, was a distinguished U.S. Congressman and respected legal mind. His grandfather, Dr. Isaac Hillyer, helped lay the foundation of Georgia’s medical frontier. It was expected, almost inevitable, that Eben would carry that torch.

The Hillyer family lineage, tracing deep Southern roots.

He wasn’t just trained; he was called. After graduating from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1853, he returned to Georgia a refined young doctor, ready to serve a region on the edge of transformation. Friends and colleagues described him as poised beyond his years, “sharp as a tack,” with a gentleness that belied his surgical skill. He was a man with a calm voice, steady hands, and a soul anchored by faith and family. By the time war broke out, he was more than prepared to serve; he was trusted to lead.

Confederate Major Eben Hillyer, Civil War surgeon and builder of 316 E 3rd Ave.

During the Civil War, he served with distinction as a Confederate surgeon, rising through the ranks due to his expertise and composure under extreme pressure. He was attached to several key Confederate units and worked in field hospitals treating mass casualties, often with limited supplies and under enemy fire. Notably, Hillyer was stationed at makeshift hospitals near Kennesaw Mountain, New Hope Church, Allatoona Pass, and Resaca, where he helped establish systems for triage and postoperative recovery long before such practices were standard.

His work was not only physically demanding but emotionally harrowing. Amputations, battlefield infections, and makeshift surgeries became daily life. Despite the trauma, he was known for his empathy and his rare ability to keep morale high among wounded soldiers. His skill and leadership earned him the respect of fellow officers and the undying gratitude of those he treated.

After the war, his contributions to Confederate medical efforts were documented in various veterans’ publications and personal letters, where comrades referred to him as a “man of both hands and heart.” His service at these pivotal battle sites left a deep mark on Georgia’s history and on Hillyer himself. By war’s end, he had not only survived but had become a symbol of medical professionalism in wartime.

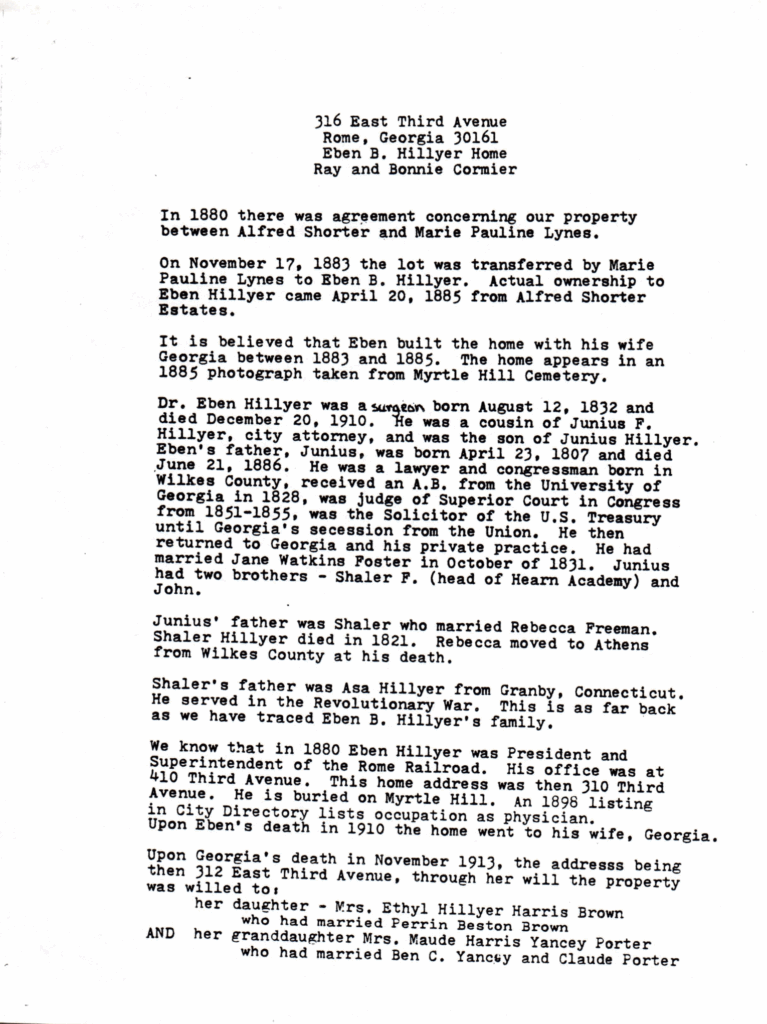

In the years following the war, Hillyer moved to Rome, Georgia, where he quickly became a civic leader. His appointment as President of the Rome Railroad in 1875 allowed him to take part in rebuilding the South’s infrastructure. He helped steer Rome’s economy toward industrial growth and connectivity. In 1883, with stability returning to the region, he commissioned the construction of this home at 316 E 3rd Ave.

Built with Victorian elegance and Southern craftsmanship, the home wasn’t just a place to live; it was a personal monument to survival, healing, and progress. In fact, Eben Hillyer even etched his name into some of the stained glass windows: a subtle, lasting signature of the man behind the house. We will be posting close-up photos of this unique detail soon.

A hand-sketched drawing of the home, recovered from the attic files.

Family Ties That Built More Than a Home

When you think about 316 E 3rd Avenue, you probably notice the beautiful details right away: the woodwork, the style, the kind of history you can almost touch. But here’s the thing: what really makes this house special isn’t just the bricks or the beams. It’s the people whose lives are woven into its story. Some lived within these walls. Others lived nearby or left their mark through family, friendship, and legacy. Together, they helped shape not just this home, but the city of Rome itself.

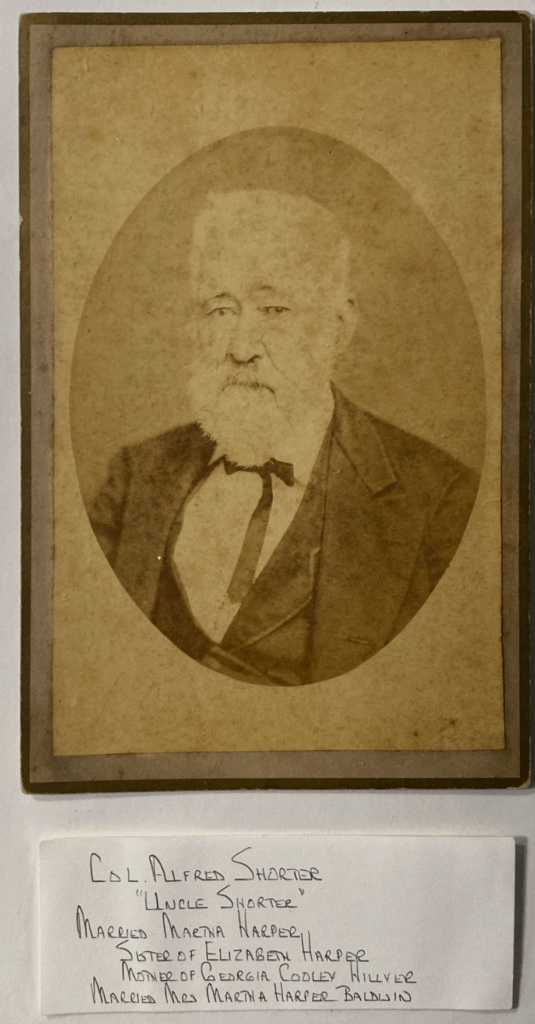

You’ve probably heard of Colonel Alfred Shorter. He was a big deal around here. He helped found what is now Shorter College and played an important role in Rome’s early history. But his connection to this house goes deeper than most people realize. Long before he settled in Rome, Shorter worked in Monticello, Georgia, alongside Hollis Cooley. Both were business associates under John Baldwin. After Baldwin passed away, Alfred married Baldwin’s widow, Martha Harper Baldwin.

Prominent Rome businessman, Confederate officer, and namesake of Shorter College, Col. Alfred Shorter played a lasting role in shaping the civic and educational legacy of Northwest Georgia.

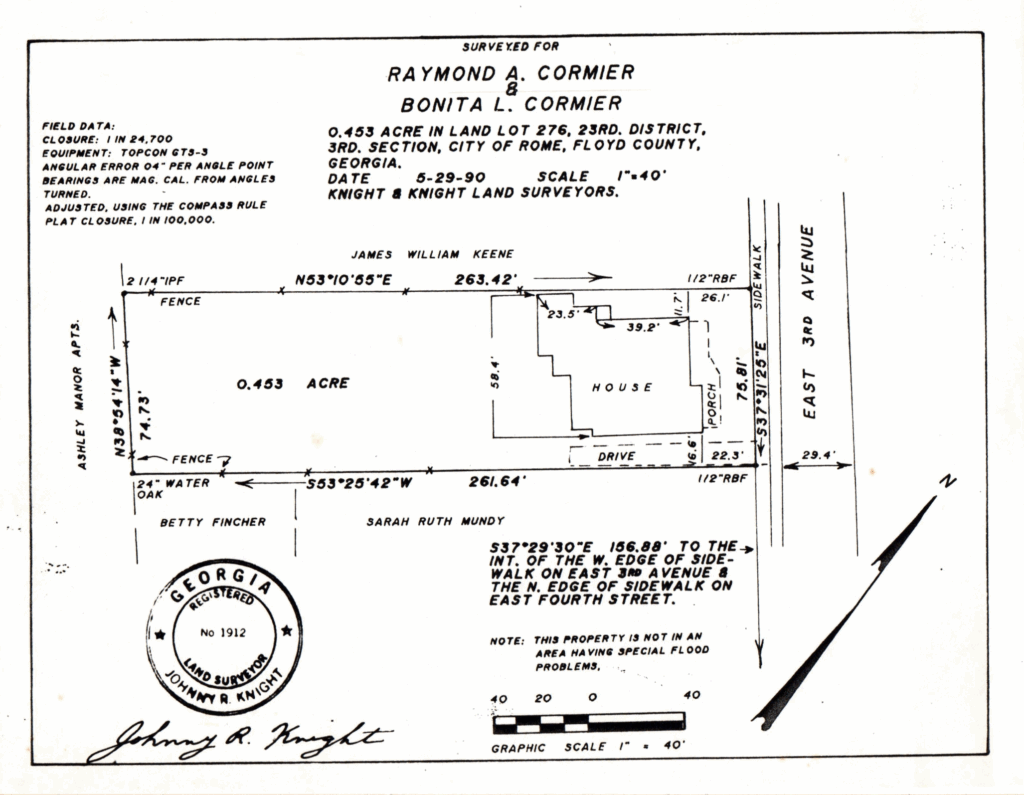

When Hollis and Elizabeth Cooley passed away, Alfred Shorter, still closely connected to the family, served as executor of their estate. He was the one who transferred the land at 316 E 3rd Avenue to their daughter Georgia Cooley Hillyer and her husband, Dr. Eben Hillyer. That exchange was not just a legal formality. It was family passing down trust and hope. The land became a place where roots could take hold, where future generations found a home.

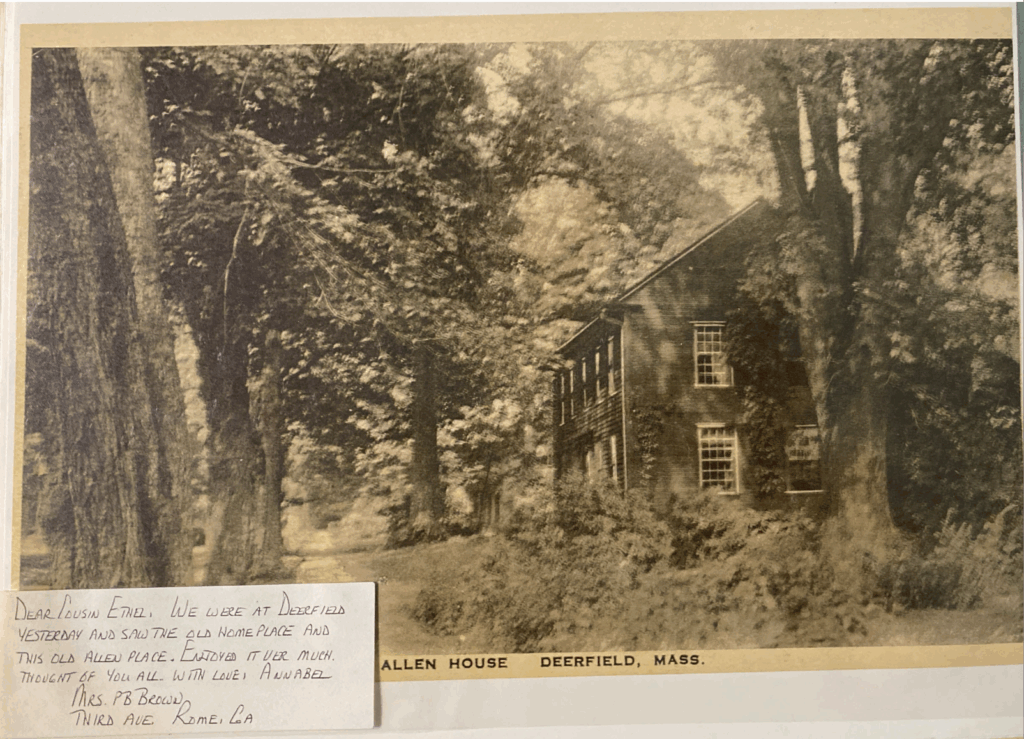

The Cooleys, though deeply embedded in Rome’s civic and social life, actually traced their roots to the North. Georgia’s father, Hollis Cooley, came from South Deerfield, Massachusetts. So even as this home was shaped by Southern tradition, its story also carried the quieter imprint of New England heritage. In a way, this house represented more than just a Southern lineage. It reflected a union of histories, of North and South, of old loyalties and new beginnings. It’s a reminder that healing sometimes happens not just in battles and treaties but in marriages, family lines, and homes built with love.

Another Cooley sibling, Ellen, married George Hillyer, a prominent lawyer and Civil War-era mayor of Atlanta. These marriages show how the Cooley family’s influence stretched beyond Rome, weaving together important figures across Georgia.

The Cooley and Hillyer families weren’t just names on a family tree. They cared deeply about education, community, and standing strong through tough times. That spirit still lives in this neighborhood. The house is beautiful, sure, but what really matters are the people who built it and kept its story alive.

Curious to see the faces behind these stories? We’ve gathered a collection of portraits featuring the Hillyer family and their extended relatives.

Nearby, the Willingham family left their own mark. Judge John H. Willingham was a respected leader who helped guide Rome through change. Like the Hillyers and Shorters, he worked hard to rebuild the city and its railroads. The Willinghams, Hillyers, and Shorters all came together to support Rome. Their stories overlap, reminding us just how much this city’s history depends on working together.

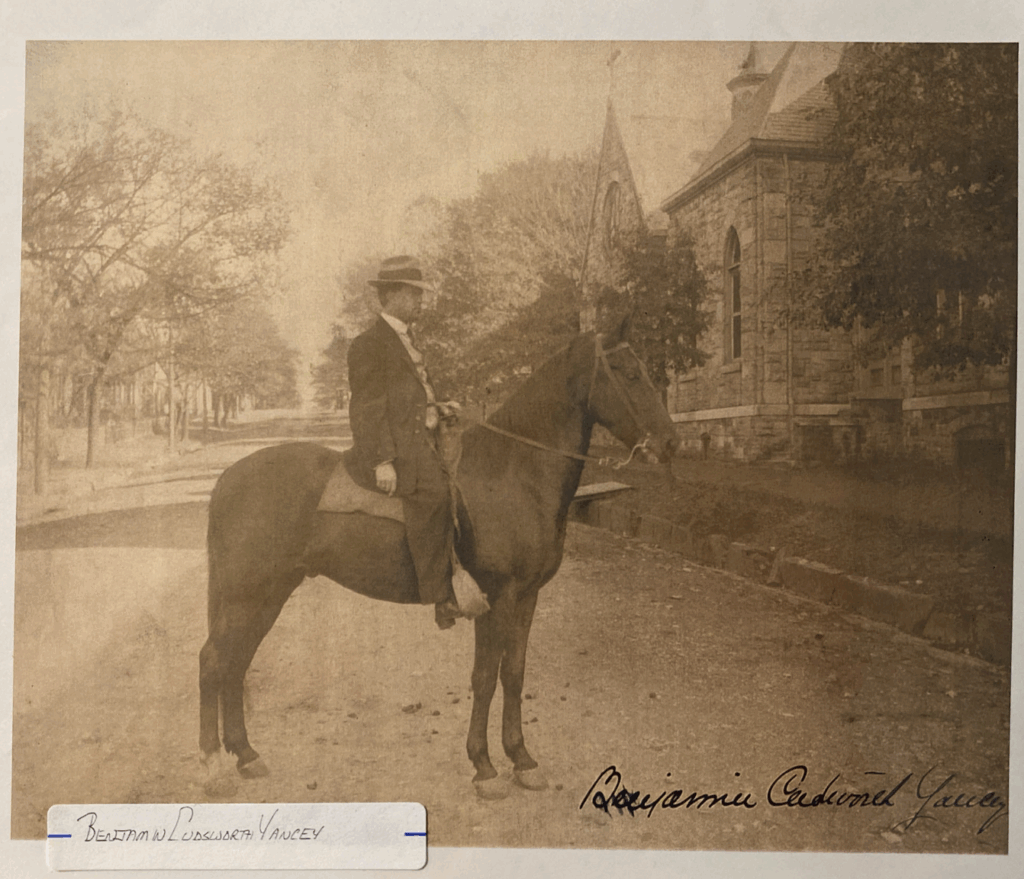

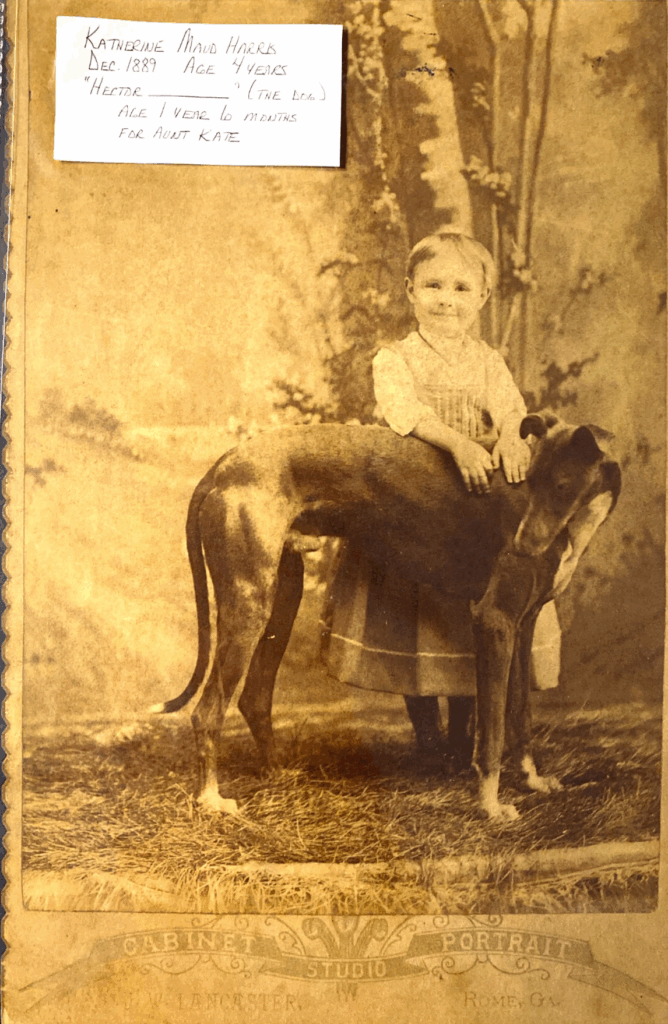

And then there’s the Yancey family. Though not tied to this house by birth, their legacy touches it through marriage and shared values. Maud Harris, daughter of Ethel Hillyer and Hamilton Harris, was born and raised right here at 316 E 3rd Avenue. Later in life, she married into the Yancey family and became Maud Yancey Porter. Through her, the Yancey name became part of this home’s living story. The Yanceys were known across Georgia for their contributions to law, diplomacy, and public service. People like Benjamin Cudworth Yancey helped shape the South’s early political landscape, leaving behind a legacy of leadership and civic duty. Even though Maud joined the Yanceys later in life, the values she carried from her Hillyer upbringing aligned naturally with the spirit of that family: steady, thoughtful, and deeply rooted in community.

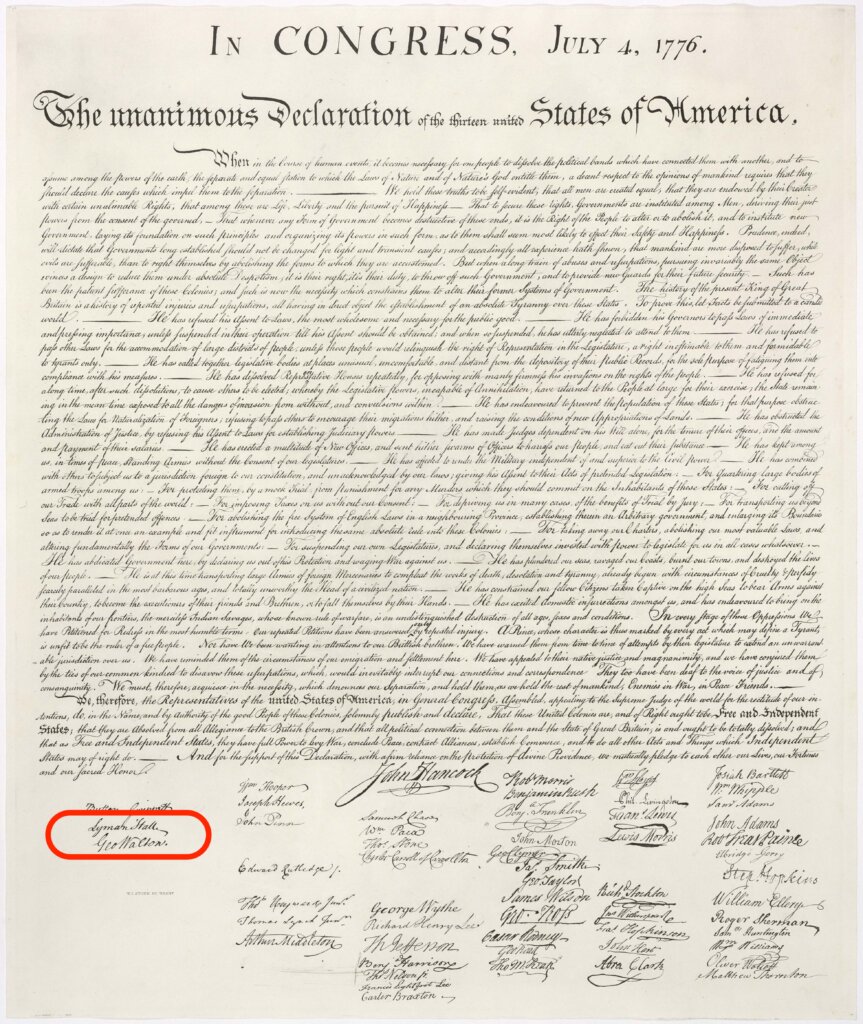

The Hillyer legacy goes even deeper than Rome. It reaches all the way back to the founding of our nation. Through maternal lines, the family at 316 E 3rd Avenue can trace its roots to two of Georgia’s original signers of the Declaration of Independence: George Walton and Lyman Hall. Walton was a prominent lawyer and statesman, eventually serving as Governor of Georgia. Hall, a physician-turned-patriot, also held the governor’s office and played a key role in founding the University of Georgia. Both men signed their names to history in 1776. Generations later, their bloodline would include Dr. Eben Hillyer, whose daughter Ethel carried this patriotic lineage proudly. In fact, it was this heritage that earned Ethel Hillyer Harris her place in the Daughters of the American Revolution. So while the signers themselves never lived at 316 E 3rd, their legacy flowed through the very people who did, turning this Victorian home into more than a local landmark. It became a living thread between Rome, Georgia, and the birth of America.

The Declaration of Independence shows the signatures of George Walton and Lyman Hall (circled for clarity). Both men were ancestors of the Hillyer family through maternal lines, linking 316 E 3rd Avenue not only to Rome’s local history but directly to the founding of our nation.

So when you step inside 316 E 3rd Avenue, you’re stepping into more than just a house. You’re entering a living thread that stretches from the birth of America to the heart of Rome. A story built by descendants of patriots, carried forward by generations who believed in something bigger than themselves. Every room reflects that quiet legacy of care, connection, and enduring strength.

1890s–1910: A Home Full of Soldiers

As Rome slowly stitched itself back together in the decades after the war, 316 E 3rd Ave stood as a beacon of both comfort and camaraderie. Major Hillyer, no stranger to pain or perseverance, transformed his home into a quiet sanctuary for those who had endured the same bloody chapters of history.

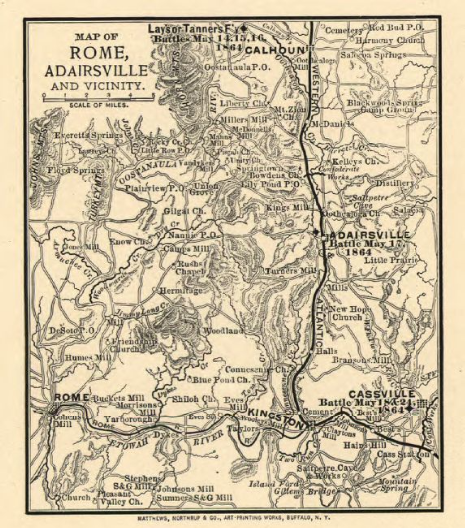

This Civil War–era map of Rome and Adairsville shows the landscape as it existed before 316 E 3rd Avenue was built. Just years later, Major Eben Hillyer would return from war and begin laying down roots here, transforming this once-battleground city into a place of legacy, family, and quiet endurance.

One particularly poignant event remains etched in the home’s legacy: a reunion dinner hosted by Hillyer for fifteen Confederate veterans. Imagine them seated around the long dining table, their uniforms faded, their stories sharp, the clink of silverware and soft laughter echoing beneath the ornate ceiling medallions. The walls, once witness to the silent tension of war recovery, now held space for healing conversations and brotherhood rekindled. What was once a house of private reflection briefly became a hall of reunion, filled with gratitude, grief, and grace.

These gatherings weren’t for nostalgia. They were for survival, moments of human reconnection for men who had seen too much. And it was here, in this house built by a battlefield surgeon, that those men were reminded what peace could feel like. Hillyer’s kindness and quiet strength made him not just a doctor or a host, but a symbol of endurance, healing, and homecoming. His legend grew not from medals, but from moments like these.

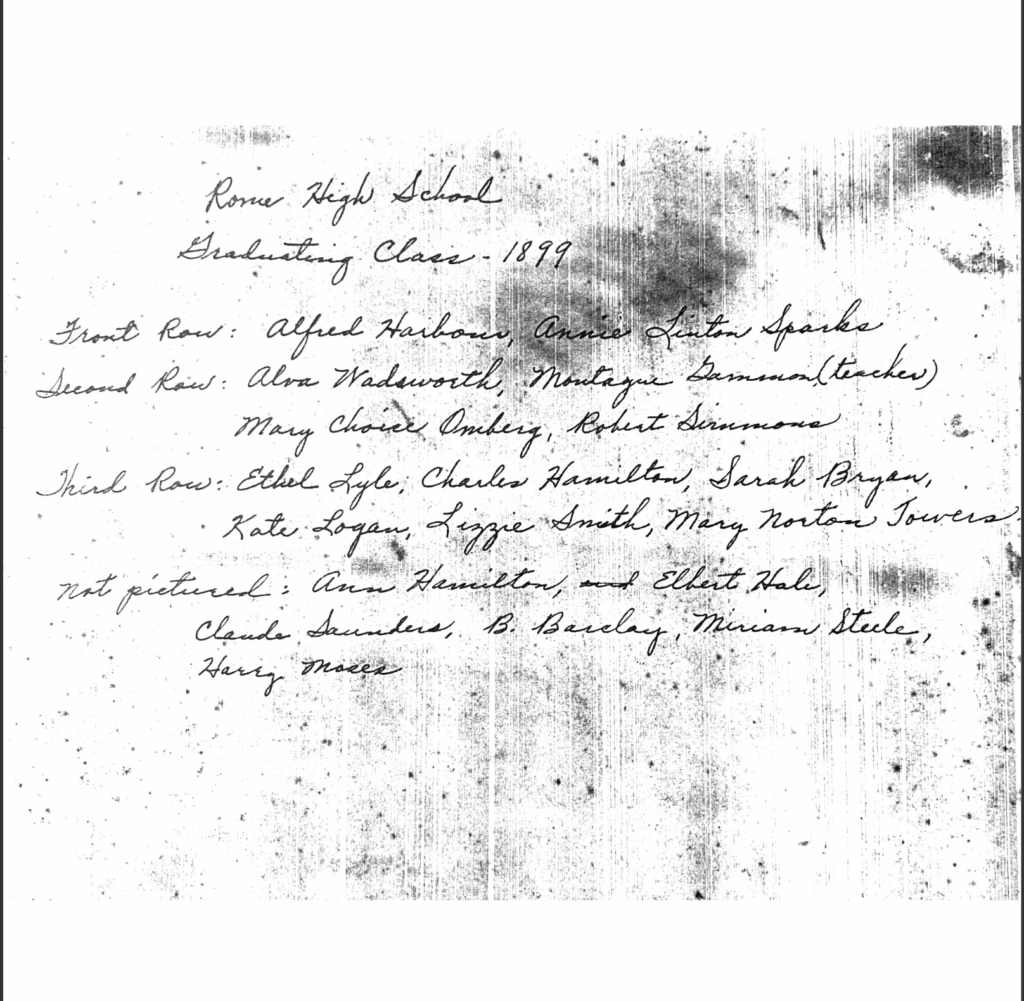

Nearby, young people were also stepping into the future. This graduating class photo from 1899 captures some of the youth from the neighborhood and the city as a whole. It reminds us that life went on, with hopes, dreams, and new beginnings blossoming even in the shadow of a difficult past.

Unearthed: The Artifacts Beneath the Soil

In 2025, while combing through the backyard with a metal detector, a friend of the current owner began pulling stories out of the ground, one rusty signal at a time. What emerged wasn’t just scrap. It was a tangible thread back to a different time. Buttons, coins, trade tokens, each small enough to fit in the palm of a hand, yet heavy with memory. These weren’t museum pieces displayed behind glass. They were carried, exchanged, maybe even lost in moments of laughter, stress, or sorrow.

- J.L.K. Pool Hall Token: This octagonal brass token, good for 2½ cents in trade, was the kind of item you’d slip into a vest pocket on your way to a smoke-filled pool hall. Dated between 1880 and 1910, it’s exactly the kind of coin someone like Major Hillyer or a visiting veteran might have dropped after an evening in town. The mystery of “J.L.K.” lingers. Was it the initials of the hall’s owner? A hidden speakeasy nickname? Either way, the token places the home squarely in the social heartbeat of post-war Rome.

- Bartlett Automotive Token: Found nearby, this aluminum token offered one dollar off a twenty-dollar purchase at Bartlett Automotive Equipment Co., located at 301 Broad Street. This wasn’t just a promo, it was part of everyday life in early 20th-century Rome. Imagine a resident from 316 E 3rd tossing this on a counter to buy a fan belt, or slipping it into a glove compartment in a Ford Model A.

- Swirled Button: Pulled from the earth with a patina only time can give, this ornate brass button may have once fastened a military coat or Sunday waistcoat. Its craftsmanship suggests the late 1800s, when clothing was custom-made and garments were passed down. Perhaps it belonged to one of the dinner guests at Hillyer’s veterans’ reunion.

- 1945 Wheat Penny: Worn smooth and caked with clay, this coin carries another story, one of endurance. It was minted the year World War II ended. This penny may have been dropped by a child playing under the porch, or perhaps by a soldier returning home. Either way, it confirms the house didn’t just survive the Civil War; it watched generations of Americans come and go.

These weren’t just old coins and buttons. They were echoes, pocket-sized proof that the past is still listening. Each one held a story: quiet in presence, rusted by time, and powerful in meaning.

1910 to 1980s: Silent Years and Shifting Hands

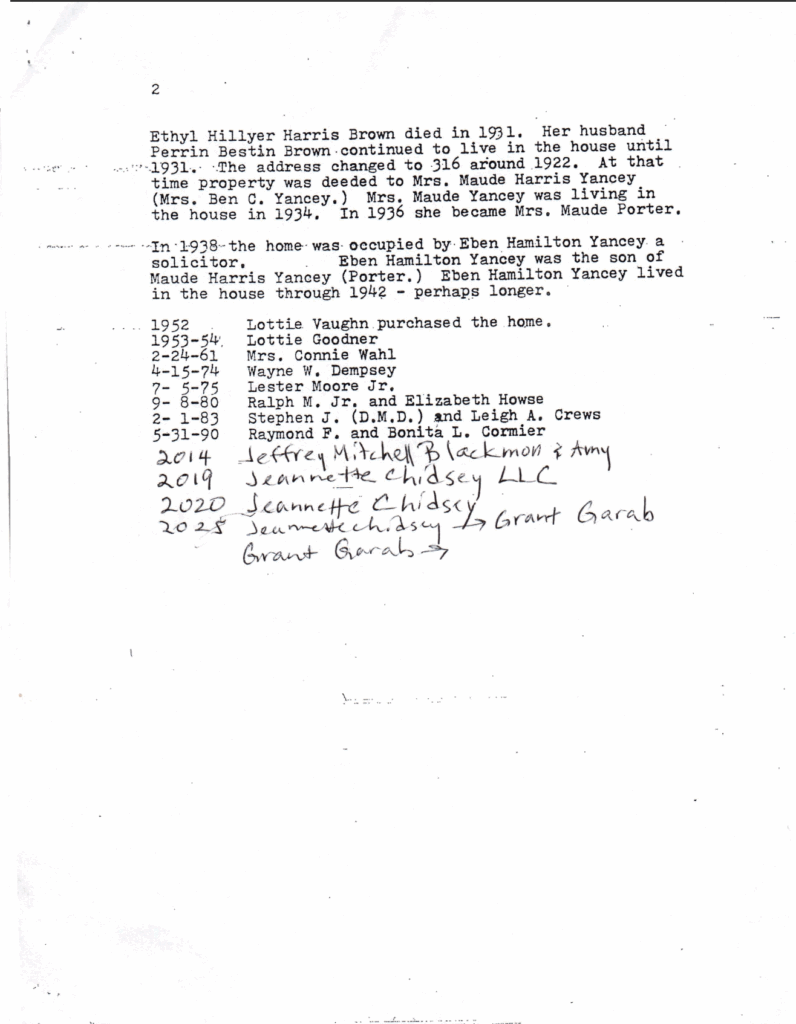

After Eben Hillyer passed away just before Christmas in 1910, the house quietly shifted from one caretaker to another. Generations moved through it, and the house subtly changed with them.

Ethel Hillyer, one of Eben and Georgia’s daughters, was born in 1860 and grew up inside these walls during a time when the South was healing and changing. She married twice, first to Hamilton Harris and later to P. Bester Brown. Though she moved away after marrying, the home where she was raised always stayed close to her heart. Ethel had a deep love for education. She served as an editor for The Roosevelt magazine, lending her voice to the cultural conversations of her time. She supported libraries, believed books could open new doors, and was active in women’s clubs and causes she cared about. Even when she was not living here, this house remained a big part of her story.

Ethel Hillyer Harris, daughter of Dr. Eben Hillyer and granddaughter of Judge Junius Hillyer, grew up at 316 E 3rd Avenue. Her childhood in the home shaped the voice that would later make her a respected figure in Southern literature.

Maud Yancey Porter was born right here in the house, the daughter of Ethel Hillyer Harris (Ethel’s name from her first marriage) and Hamilton Harris. Maud spent most of her life on 3rd Avenue. Her family roots ran deep in Rome. Her granduncle, Colonel Alfred Shorter, founded Shorter College, so education and service were part of her family legacy. Maud married Judge Claude H. Porter and remained on 3rd Avenue until illness forced her to leave in later years. Known for her calm faith and welcoming kindness, she was deeply involved at First Baptist Church, leading ladies’ Bible study groups and directing music for the Sunday schools. Those who knew her remember her warmth and generosity, qualities that echoed the spirit of this home.

During the 1930s, as families and cities across the country adjusted to the challenges of the Great Depression, 316 E 3rd Avenue also changed. The large single-family home was divided into apartments, a practical shift that allowed the space to continue serving people in a new way. For decades, the house held layers of life; multiple families living under one roof, each adding their own rhythm to the story. Yet even as the floor plan changed, the heart of the home remained.

Many members of the Hillyer family, including Major Eben Hillyer and his descendants, are buried at Myrtle Hill Cemetery, which rests prominently atop one of Rome’s scenic hills. Their headstones stand as quiet reminders of a family deeply woven into the city’s history and heritage. We will be adding photos of these headstones here soon to give a closer look at this lasting legacy.

1980s to 2000s: The Cormier Preservation Era

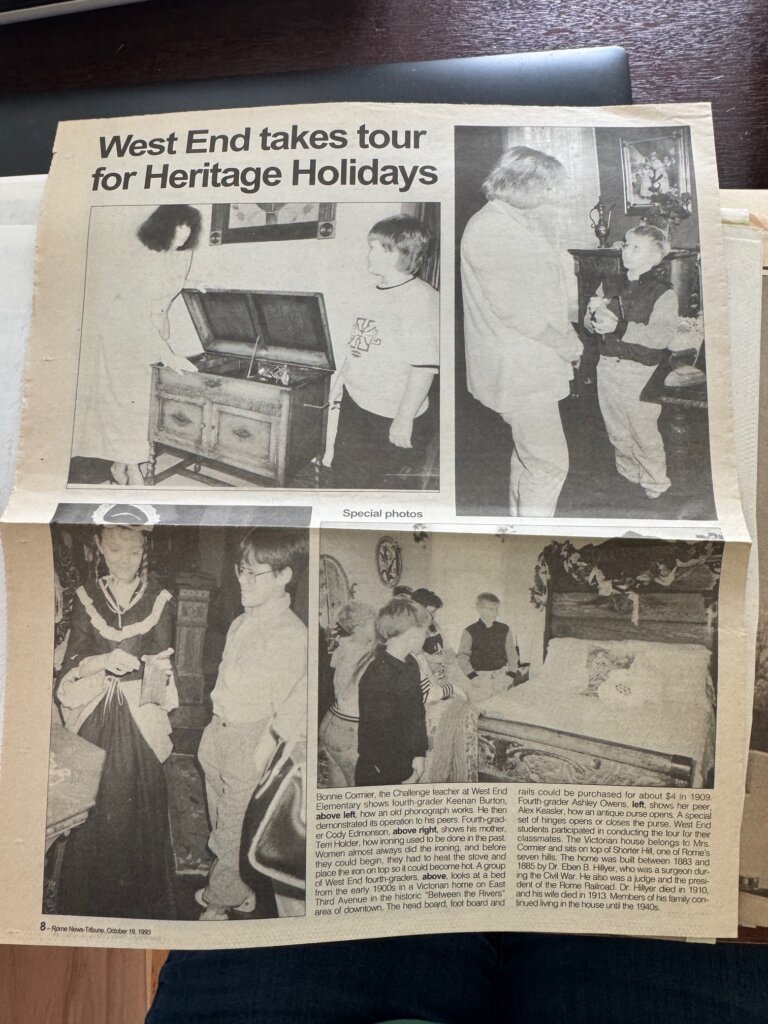

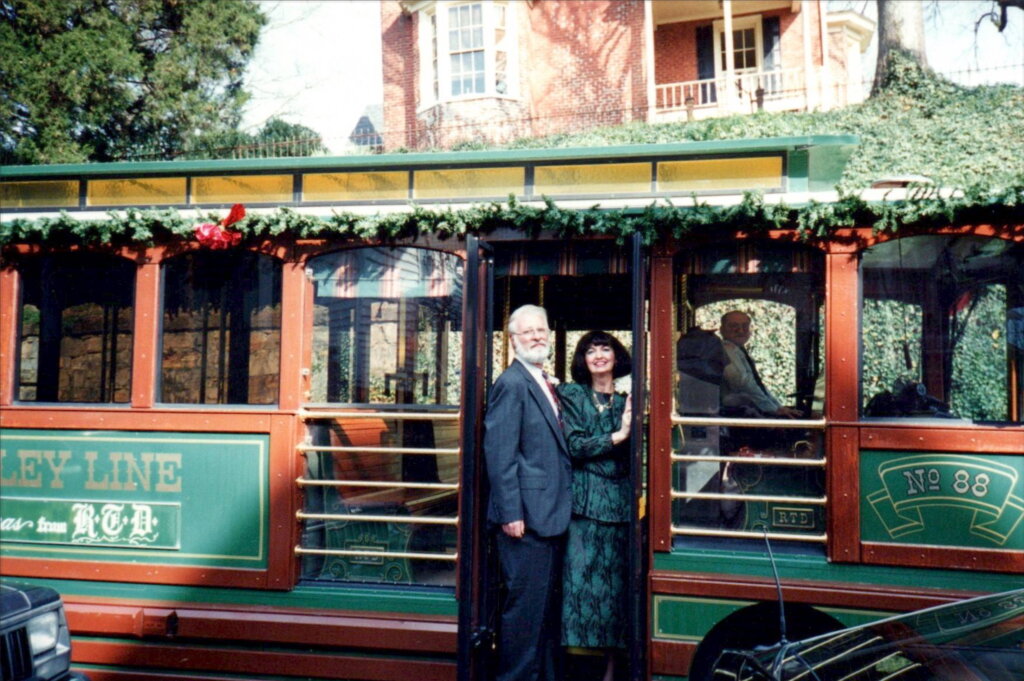

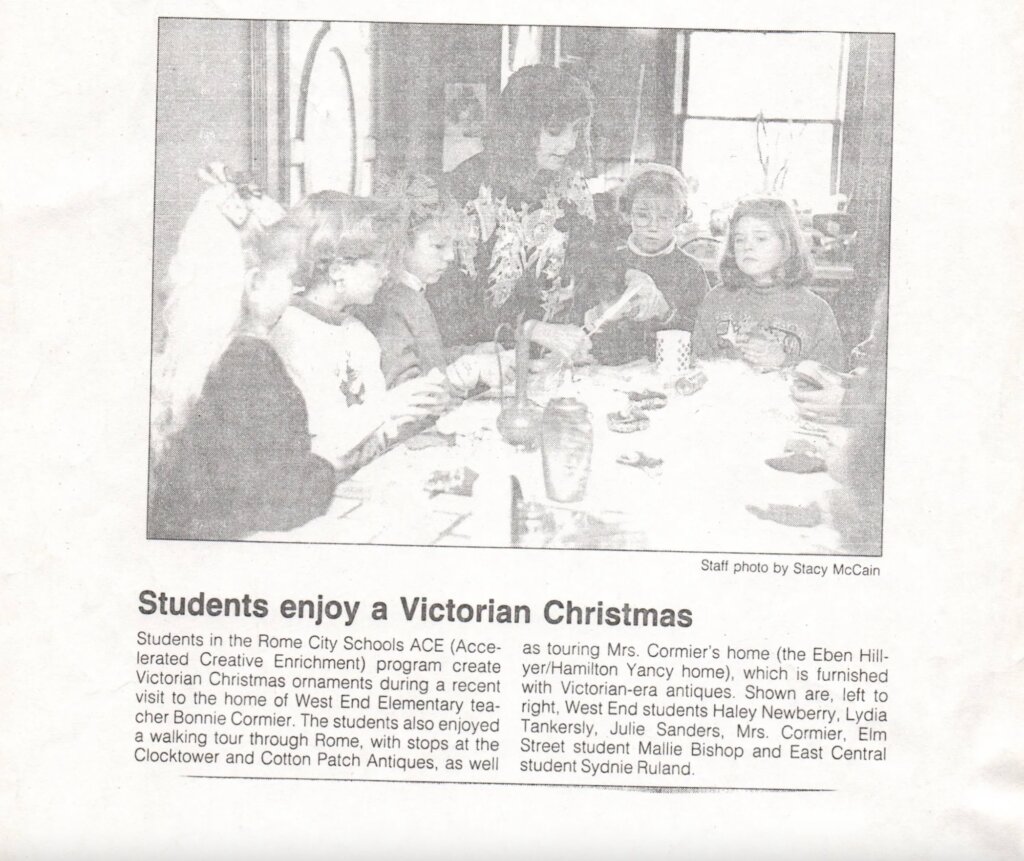

Bonnie Cormier brought the home into a new light. A passionate preservationist, she saw beyond the aging wood and faded wallpaper. Bonnie saw a story still worth telling and fought to make sure it wasn’t forgotten. She opened the house for tours, proudly guiding guests through each room with a reverence that felt almost sacred. To her, 316 E 3rd Ave wasn’t just an old Victorian; it was a heartbeat, a living thing that had seen generations rise, fall, and find their way home.

Bonnie Cormier leads a special tour of her historic home at 316 E 3rd Avenue for her elementary school students, sharing stories and history from the neighborhood.

Through letters to editors at Victorian Homes magazine, she championed the house’s inclusion in national preservation conversations. Her notes, some charming, some bold, reflect a woman determined to restore dignity to both the home and the story behind it. She poured her soul into organizing photo documentation, historical records, and a tour script that read like a love letter to the past.

She poured her soul into organizing photo documentation, historical records, and a tour script that read like a love letter to the past.

Preserving 316 E 3rd Ave has always been about more than just maintaining its beautiful woodwork or keeping the walls standing. It’s a way of honoring the lives and memories that fill every room. Each owner who has cared for this home became a storyteller, passing down not just a building, but a living legacy, a way to keep history alive for future generations to discover and cherish.

What Bonnie preserved wasn’t just architecture. It was memory. It was meaning. And in many ways, she passed the torch to those now telling the home’s story today.

2010 to 2025: From Blackmon to We Are Home Buyers

Over the past 15 years, 316 E 3rd Ave has seen a quiet renaissance through the hands of those who cherished its legacy. Each owner, in their own way, contributed to preserving and enhancing what makes this home so special.

Jeffrey and Amy Blackmon (2014) began the process of bringing the house back to life, maintaining many of its period features while making it more livable for modern times. They were stewards of its character, ensuring that every change honored its Victorian bones.

Jeannette Chidsey (2019) added her own chapter by continuing the upkeep and protecting the home’s integrity. From refinishing original surfaces to preserving antique elements, her care helped stabilize the home through the decade.

We Are Home Buyers, LLC (2025) stepped in with a vision to preserve not only the house but the rich narrative behind it. With a passion for history, the current owners have added structural upgrades like a new retaining wall and brought the home’s story into the digital era, allowing the public to engage with its past like never before.

Today: A Museum With a Pulse

316 E 3rd Ave is no longer just a house; it’s a living museum. Every token, button, and handwritten letter tells a chapter in its ongoing story. It’s a home that has endured war, welcomed returning veterans, been cherished by preservationists, and brought into the digital age by people who believe the past should never be boxed up and forgotten.

The well-worn banister, the delicate ripple in the original glass panes, and carefully preserved documents tucked away; they all breathe life into the narrative. They remind us that history is not always found in textbooks. Sometimes, it’s right under your feet. Sometimes, it’s buried in the backyard, waiting for the right hands to bring it back to light.

So the next time someone asks you about this house, don’t just say, “It’s an old place in Rome.” Tell them it was built by a Confederate surgeon who saw the worst of war and chose to build something better. Tell them it may still cradle the pocket change of Major Eben Hillyer himself. Tell them the ground still speaks, and now, so do you.

As we continue to explore the rich history of 316 E 3rd Avenue, this page will be updated regularly with new stories, discoveries, and insights. We’re especially excited to soon speak with Bonnie Cormier herself, whose firsthand memories of living in the house will add an insider’s perspective to this ongoing journey.

Ready to Sell Your Historic Property? We Are Home Buyers Can Help!

Do you own a historic home and want to sell it fast for cash? We’re here to help preserve its story while making the sale simple and stress-free. Reach out today to get started!